The library at the academic institute where I work part-time recently had a massive chuck-out. Scanning the tomes strewn across the tables, I was struck by the high proportion of reference books - encyclopedias, dictionaries, guides, thesauruses, -ographies of various types. Quite a few seemed to be just lists bound between hard covers - an inventory of modernist sculptures made in the UK between 1945 and 1972 along with their current institutional location; a list of works by female visual artists; a cataloguing of examples of land art.

Reference books used to be one of the most reliable generators of revenue within publishing. The sheer number of libraries around the world provided a guaranteed base level of sales, and there were other institutions that might have a specialist interest in particular reference works. Back then, you could also probably count on some individuals buying them as well - people with professional or obsessional reasons. Then with general knowledge encyclopedias, there was the association of owning a set with self-advancement and edification.

But it was the profusion of specialized reference works that grabbed my eye as I browsed the bargain-price tables in the library. It seemed to me that it must have been such a thriving market that publishers of these kinds of books were incentivized to come up with new subjects and concepts for reference works, to the point of inventing needs and desires that didn't necessarily exist until the idea was put out there. How else to explain some of the titles that I saw - like the Dictionary of Literary Characters. Or like these -

But thinking about it, for a drama school or a university theatre department, having these in book form would be much more preferable in terms of ease of use than having to scroll through back issues of the New York Times on micro-film. Each edition of the Times is vast and on micro-film there would be legibility issues. Ergonomically, and in terms of eye strain, micro-film readers are a nightmare.

The stuff in this stacks-clearing sale was going dirt cheap and I was sorely tempted to rescue some of the orphaned tomes - but I was put off by the sheer weight of them (going to this place of work involves a lengthy commute by public transport) and also the knowledge that - after an initial flick-through - I would almost certainly pile them up in some corner and never look at them again, The house is already horribly cluttered - I must have around 400 unread books.

Still, there was something melancholy about these bereft books - I thought of all the effort, diligence, care that must have gone into their laborious construction. The sense of responsibility, based in the belief that what was being undertaken was of real value. And I'm sure they were valuable to users. Remember just how hard it was to find things out before the internet.

Of course, pathos suffuses the objects in any second-hand store - books, records, magazines, whatever. You think of the creative excitement behind each object - the labour not just of the authors but of everyone involved in making a project reach fruition and get out into the world: editors, designers, marketing etc. The anticipation of impact. DJ Shadow's comment comes to mind - about the record store basement as "a big pile of broken dreams".

But with music, there is still the possibility of a life in the culture - radio play or streams or YouTube views... crate-diggers unearthing things and sampling, bringing it back into circulation if often anonymously. The analogue husk of the music is not necessarily the end of the story. Fiction and non-fiction can get reissued or rediscovered by new readers. But reference books - here, it's the very function that has been voided. The internet has usurped the role of the bound ink-and-paper repository of information.

Before the internet took over, back in the 1990s, one of my main ways of procrastinating - putting off the work that needed to be done - was to pull a reference book off the shelves and flick through it. usually something to do with music. Often it was the Rolling Stone Albums Guide, which had somehow come into my possession - it's not something I would have bought. I'd skim through it and my eye would come to rest on an entry for the Allman Bros, or Bloodrock. Or I'd reread and be freshly bemused by the loathing directed at Sparks, or snort once again at the measly 3 out of 5 stars afforded My Bloody Valentine's Isn't Anything.

Chuck Eddy's "guide" to greatest heavy metal albums was another thing that was good for dipping into.

Thinking back to much earlier in my life, certain reference works were revelatory. Take The Visual Encyclopedia of Science Fiction - a thick, full-color book teeming with illustrations and reproduced covers of paperbacks and s.f. magazines, but also crammed with well-written, informative essays on various sub-genres and scenario typologies, and mini-thinkpieces by some of the great writers in the field (there's a terrific one by J.G. Ballard on the cataclysm novel).

The Visual Encyclopedia of Science Fiction was a present I asked for for my 14th birthday, or maybe it was Christmas 1977 - I'm not sure. Another present request was a pictorial dictionary - the one below. See, I fancied being able to recognise and name things like, say, all the different parts of a shoe, and to know all the different kinds of shoe as well... basically have at my command the names of appliances and tools and vehicles and garments and plants and creatures and ... every kind of object and substance in the world.

However although I never got rid of it - and recently was reunited with the book after years of it languishing in storage - I have never once found myself using The Oxford-Duden Pictorial English Dictionary. So I still couldn't identify the different bits of a shoe or name many types of footwear. I guess there's still time...

Still, perhaps there remains some demand out there for these kinds of work in solid form, use that is still made of them.

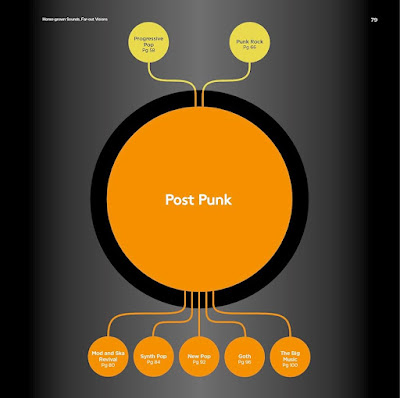

Indeed recently I was hired to do some consultation on a music encyclopedia (it just occurred to me I have no idea if it is ever going to exist in paper-and-ink form or is just going to be available online, through subscription). I also contributed a few entries.

Back in the 1990s, I did some things for Encyclopedia Britannica. The entries can be found online, credited to Simon C.W. Reynolds - but they have been updated by unknown hands, so after a certain chronological point in each entry, the style - and the opinions - are no longer mine. (Of course, they were probably not meant to have discernible personal style or a non-objective perspective in the first place). I don't know if any of these entries ever made it into the book form of the Britannica. Obviously I quite fancied the idea of being in this gigantic set that door-to-door salesmen used to flog to families who saw knowledge as aspirational, a form of status.

Then there's the Spin Alternative Record Guide, where being opinionated was valued, although there was also an emphasis on encyclopedic comprehensiveness (every last release by an artist had to be at least listed at the top of the entry and graded - but ideally mentioned in the entry itself, even if only passingly). There was also an element of faux-objectivity maintained for the grades awarded each recording (we as contributors were instructed to be restrained with our 10 out of 10s... but the editor was noticeably generous with his own favorites).

People of a certain age have testified what a lifeline the Spin Alternative Record Guide was in those days just before the Internet took off - especially if you lived somewhere remote. For there were no easily accessible sources of information or guidance when it came to left-field music. But beyond that the Guide was something to read for the pleasure of reading. The contributors were the best in the American business at that time - and they were expected to be stylish and individual rather than restrained and quasi-objective.

And there are other reference works that count as literature, guide books where the compiler's personality suffuses every sentence. Most famously: David Thomson's A Biographical Dictionary of Film. A flickable feast of perceptions and descriptions to savor, sat right alongside gluey globs of facts (every last film a director made, an actor starred in).

I also love Have You Seen...? - DT's twist on the 1000 You Must See/ Hear / Read Before You Die format. I'm always blown away by the way DT deftly threads together background stuff about the making of pictures (money, the process of a script coming into being, disagreements over casting, conflict on the set) with aesthetic responses, zooms into details of scenes or performances, where a movie sits in the arc of a director's work, meta-thoughts about the nature of cinema. Here, reference and reverence, usefulness and ecstasy, coexist.

.jpg)