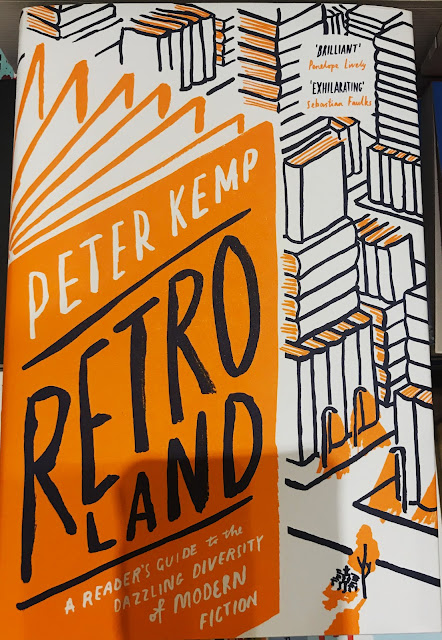

A book whose title caught my eye while in the UK last week - understandably!.

Presumably a play on Betjeman's Metroland.

Publisher's blurb:

Over the past fifty years, fiction in English has never looked more various. Books bulkier than Victorian three-deckers appear alongside works of minimalist brevity, and experiments with form have produced everything from verse novels to Twitter-thread narratives. This is truly a golden age. But what unites this kaleidoscopic array of genres and styles? Celebrated writer and critic Peter Kemp shows how modern writers are obsessed with the past. In a series of engaging and illuminating chapters, Retroland traces this novelistic preoccupation with history, from the imperial and the political to the personal and the literary. Featuring famous names from across the United Kingdom, United States, and the wider Anglophone world, ranging from Salman Rushdie to Sarah Waters, Toni Morrison to Hilary Mantel, this is a work of remarkable synthesis and clarity—a wonderfully readable and enjoyably opinionated guide to our current literary landscape.

The Telegraph says:

Peter Kemp has written a history of the English novel since 1970. (Retroland describes itself as a history of fiction in English, but doesn’t refer to short fiction, and hardly touches on North American, Australian, or even Scottish or Irish writing.).... Another history might have considered the impact on fiction of debates about cultural appropriation, and certainly the internet and social media.

Kemp’s overall analysis is that fiction in English has been driven by an obsession with the past. In particular, he says that historical fiction is now at the centre of fiction’s achievements. His second contention is that fiction in English started to be written by subjects of the old empire with invigorating effect.

....This might have been a contribution to the debate if it had been written when it was first conceived of. As it is, it bears all the marks of a manuscript tinkered with over decades, the mind and opinions of its author never shifting from those far-off days or paying attention to major developments. A history of contemporary fiction from a book reviewer who, fundamentally, is rather scared of new things.

The Guardian also quite caustic:

a pell-mell survey of the past half-century of British fiction... it sets out to argue that modern novels are overwhelmingly preoccupied by the past; a thesis that’s persuasive enough, and one that possibly goes some way to explaining why, come Booker time, writers who buck the trend by staying in the here and now – Gwendoline Riley, Sarah Moss, Ross Raisin – seldom get a look in.

Kemp’s tantalising introduction sketches the extent of what his subtitle dubs the “dazzling diversity” of fiction in the period at hand, taking in “a novel that uses only the 483 words spoken by Ophelia in Hamlet” (Let Me Tell You by Paul Griffiths), another “narrated by the first edition of Joseph Roth’s 1924 novel Rebellion” (Hugo Hamilton’s The Pages), and another “that excludes the verb ‘to have’” (Next by Christine Brooke-Rose). Yet you won’t find any of them in Retroland proper, home, instead, to discussions of Midnight’s Children, Atonement, Possession, et al – not so much off the beaten track as stuck on the M25.....

But no matter; you read on eagerly, keen to know Kemp’s explanation for the patterns he justly identifies: the “pervasive[ness of] the dual-narrative, double time-scheme novel which juxtaposes a contemporary story with one set in an earlier era” (yes! What’s with that?); the ubiquity of the “trauma plot” (ditto); and the enduring 90s revival of historical fiction, which the late Helen Dunmore attributed to pre-millennial anxiety about what lay ahead in “the blank, silent sheet of years around the corner”.

.... Despite the setup, Retroland is really a pretext for a whistlestop tour of dozens of novels loosely bunched into four groups –novels of empire, novels of “buried trauma”, novels about history and novels built on older novels (such as Smith’s On Beauty, pegged to EM Forster’s Howards End, or Jeanette Winterson’s Frankissstein), all of which rush by in a largely contextless blizzard of titles, names and plots, with next to nothing by way of logical signposting....

About his subject, Kemp knows all there is to know – that’s clear – yet as a tour guide he left me muttering at the back of the group, itching to sneak away to the dodgier locales we’re warned off....

Sometimes Retroland reads less like a literary-critical survey than the minutes of a 50-year colloquy between every author who ever put pen to paper: ... When Kemp segues from Sarah Waters’s The Night Watch to The Little Stranger to The Paying Guests to Alan Hollinghurst’s The Stranger’s Child and The Sparsholt Affair, or from John Lanchester to Zadie Smith and Sathnam Sanghera, or from Francis Spufford to Carys Davies and George Saunders, he’s just pasting his old Sunday Times reviews right in. Those examples account for about 10% of the text and there’s a lot more where they came from – he’s been reviewing for 40 years....

Did Kemp think no one would notice that Retroland is substantially an elaborate patchwork of self-plagiarism? Or does it not matter?... Did Kemp (or his editor) even figure out who Retroland was for? Either way, it’s a runaway train – and the carriages are full of recycled plot summary.

Irish Times is kinder

"Kemp's loose thesis – the past is a present country – leads us to some good writing (his own included)"

No comments:

Post a Comment