"We spend our days in front of screens which broadcast us more information than we’re able to handle about things we aren’t able to change. Is it any surprise that safe and familiar relics are being dug up to soothe us?" - Olivia Ovenden

What with being Mr. Retromania, I am quoted in Ms. Ovenden's Esquire piece "The Pull Of The Past: How We All Got Hooked On Nostalgia In The 2010s", an interesting deep dive into the memory-surfacing algorithms of social media etc, with a particular focus on Nineties-nostalgia and the widespread recourse to Friends as a sort of televisual eqivalent to ambient / Ambien.

Wednesday, December 25, 2019

Friday, December 20, 2019

Hauntology Parish Newsletter - Bumper Yuletide Edition

Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in!

Moon Wiring Club cometh with his customary seasonal offering: Cavity Slabs. Like the atypical summertime long-player Ghastly Garden Centres of earlier this year, Slabs is a brisk and beat-driven effort, veering away from the boggy hinterland of ambience and vocal gloop into which much of Ian Hodgson's output this past decade has sunk so deliriously. Focused and concise, the new record boasts just eight tuff tunes. The reference point this time around is breakbeat hardcore - in moments, I'm reminded of the phat-but-spooky sound of Eon, although Ian says the launchpad for the new direction was actually this obscure tune:

This very very early Moving Shadow track (by a group later and slightly better known for their Rising High releases) first reached Ian's eardrums via an Autechre radio show from many years ago. "It always stuck with me. It’s that mix of beats with ‘anything goes’ sampling and environmental sounds ~ it always makes me think of coastlines... and a sort of grey mistiness."

The aim with Cavity Slabs was to take a detour round the ongoing overload of rave-replicas, with their neurotic attention to period detail and naked nostalgia, and instead reactivate the bygone playfulness and incongruous-samples-clumsily-collaged approach of the early Nineties, which threw up so many genre-of-one anomalies and half-realised oddments alongside the classic bangers and slammers.

"I wanted to compose something that reflected the dankness / mystery of fog without it being an ambient drone affair," adds Ian. The name Cavity Slabs comes from a pile of building materials Ian passed on a rainy-day stroll, which conjured associations both of vinyl platters and "limestone moorside and burial chambers". The overall atmosphere and thematic is caught in the slogan "COAX ANCIENT VOICES FROM THE LANDSCAPE" and track titles like "Cromlech Technology" - cromlech being a megalithic altar-tomb or circle of standing stones around a burial mound.

Cavity Slabs is available for purchase here .

But wait... there's more... adding to the Xmas feast, there's a new, radically different version of an old MWC fave: a DL-only VULPINE REDUX edition of Somewhere A Fox Is Getting Married. "The original album plus 47 minutes of 12 bonus track alternate takes / extended versions / tangentially related nonsense from the vaults circa 2006-2011" including unreleased experiments like "35 Year Sit Down" and the lost "Schlagerdelia" classic "Mountain Men".

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Talking of "grey mistiness" - remiss have I been in not alerting parishioners to this new release by Lo Five - Wirral-based electronician Neil Grant.

There's a really nice "mundane mystical" atmosphere to the sound Neil's worked up on his lovely new album Geography of the Abyss - muzzy textures like looking out through a coach window that's streaked with rippling rivulets of heavy rain, or trying to peer through the frosted-glass window of your front door to see who's coming up the path. The vibe of the album reminds me of the sort of trance you can fall into while travelling on a train or a bus, that feeling of slipping outside the moorings of time.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

A record that not only remissly passed without comment from me, but that I missed completely when it originally came out in June - Vanishing Twin's The Age of Immunology.

Triffic stuff - at times like The Focus Group if based around "proper" musicianship rather than sampladelia. As with their previous album Choose Your Own Adventure, the starting points of Broadcast, Stereolab, White Noise, library music, etc, are still discernible, but now they are definitively on a journey of their own.

‘You Are Not an Island’, ‘Invisible World’ and ‘Planete Sauvage’ were apparently "recorded in nighttime sessions in an abandoned mill in Sudbury"!

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

More remissness - alert overdue for the release of the audio element of Andrew Pekler's wonderful Phantom Islands - A Sonic Atlas project of last year.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

A recommendation from parish elder Bruce Levenstein

Release rationale:

Mount Maxwell continues his run of 1970s themed releases with a full length meditation on the perceptual experiences of children born in the wake of the 1960's cultural revolution. Highly ambivalent in tone, Only Children marks a departure from earlier MM releases both in its use of acoustic instruments and in a newfound sense of criticality towards its subject matter; the back-to-the-land optimism of tracks like 'Nature ID' in uneasy proximity to the skeptical disquiet of 'Weird Places' and 'Nomad'.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Bruce also brings to my attention this effort

Release rationale:

There was a certain something about watching television in the 70s and 80s. The static crackle when you switched on your set. The faint smell of ozone as it slowly warmed up. The chunky buttons (including such flights of fancy as 'BBC3' and 'ITV2"). And, of course, the programmes themselves.

Whether it was HTV's seminal Folk Horror tinged children's classics 'Sky' or Children of the Stones, BBC1's fiercely intelligent 'adult-show-for-kids' 'The Changes' or ITV's everyday tale of alien possession, 'Chocky', the era was bursting with inventive, unforgettable and yes, terrifying shows.

The only thing more memorable than the actual programmes were their theme tunes. The unique talents of Paddy Kingsland, Sidney Saget, Eric Wetherell, John Hyde and many more were responsible for the atmospheric, eerie soundscapes which formed the aural backdrop to our favourite shows. Which is where Kev Oyston (The Soulless Party) and Colin Morrison (Castles in Space) come in. They've corralled the best of today's innovative electronic musicians, and together they've created 'Scarred For Life: The Album', a collection of new music inspired by the terrifying televisual sounds of our childhoods.

All proceeds for this album will go to aid Cancer Research UK, a charity which is close to the hearts of some of our artists, one of whom is currently undergoing treatment for cancer.

Enjoy. And remember: DO have nightmares. They're good for you.

-Stephen Brotherstone & Dave Laurence, co-authors 'Scarred For Life Volume One: the 1970's'. .

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

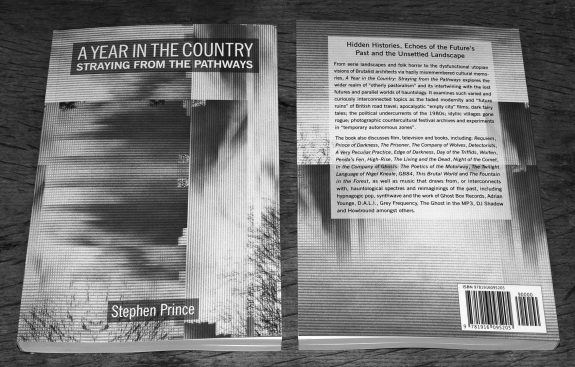

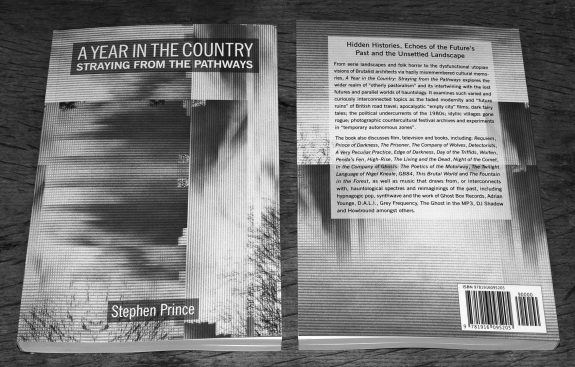

The incredibly prolific and thorough Stephen Prince of A Year in the Country - independent scholar of the rustic eerie and convenor of reliably interesting compilations - has just published a second book.

Straying From the Pathways: Hidden Histories, Echoes of the Future's Past and the Unsettled Landscape is the companion volume to last year's Wandering Through Spectral Fields: Journeys in Otherly Pastoralism, the Further Reaches of Folk and the Parallel Worlds of Hauntology.

How does Stephen do it?!?

More information about Straying From the Pathways here.

Hark at this here Table of Contents!

1. Explorations of an Eerie Landscape: Texte und Töne – The Disruption, The Changes, The Edge is Where the Centre is: David Rudkin and Penda’s Fen: An Archaeology, The Twilight Language of Nigel Kneale, The Stink Still Here – the miners’ strike 1984-85 – Robert Macfarlane – Benjamin Myers’ Under the Rock: The Poetry of a Place

2. Fractured Dream Transmissions and a Collapsing into Ghosts: John Carpenter – Prince of Darkness, Halloween III: Season of the Witch, Village of the Damned, Christine – Nigel Kneale – Martin Quatermass – John Wyndham’s The Midwich Cuckoos

3. Hinterland Tales of Hidden Histories and Unobserved Edgeland Transgressions: Adrian McKinty’s In the Morning I’ll Be Gone – Clare Carson’s Orkney Twilight – David Peace’s GB84 – Tony White’s The Fountain in the Forest

4. Countercultural Archives and Experiments in Temporary Autonomous Zones: Jeremy Sandford and Ron Reid’s Tomorrow’s People – Richard Barnes’ The Sun in the East: Norfolk & Suffolk Fairs – Sam Knee’s Memory of a Free Festival: The Golden Era of the British Underground Festival Scene – Gavin Watson’s Raving ’89 – Molly Macindoe’s Out of Order: The Underground Rave Scene 1997-2006

5. The Village and Seaside Idyll Gone Rogue: Hot Fuzz – The Avengers’ “Murdersville” – The Prisoner – In My Mind – Malcolm Pryce’s Aberystwyth Mon Amour

6. Albion in the Overgrowth and Timeslip Echoes: Requiem – The Living and the Dead – Britannia – Detectorists

7. In Cars – Building a Better Future, Peculiarly Subversive Enchantments and Faded Futuristic Glamour: In the Company of Ghosts: The Poetics of the Motorway – Joe Moran’s On Roads: A Hidden History – Chris Petit’s Radio On – Autophoto – Martin Parr’s Abandoned Morris Minors of the West of Ireland – The Friends of Eddie Coyle – Killing Them Softly – Langdon Clay’s Cars: New York City 1974-76

8. Brutalism, Reaching for the Sky and Bugs in Utopia: Peter Chadwick’s This Brutal World – Bladerunner – J.G.Ballard – Ben Wheatley – High-Rise – Peter Mitchell’s Memento Mori – Brick High-Rise

9. Battles with the Old Guard and the Continuing sparking of Vivid Undercurrents: A Very Peculiar Practice – Edge of Darkness

10. Lycanthropes, Dark Fairy Tales and the Dangers of Wandering off the Path: The Company of Wolves – Danielle Dax – Red Riding Hood – Wolfen – Hansel & Gretel: Witchhunters – The Keep

11. The Empty City Film and Other Visions of the End of Days – Survival and Shopping in the Post-Apocalypse: Day of the Triffids – Into the Forest – Night of the Comet –The Quiet Earth

12. Universe Creation, Spectral Lines in the Cultural Landscape and Reimagined Echoes from the Past: Hauntology – Hypnagogic Pop – Synthwave – D.A.L.I.’s When Haro Met Sally – Nocturne’s Dark Seed – Beyond the Black Rainbow – Mo’ Wax, UNKLE, Tricky, Massive Attack, Portishead, DJ Shadow, Andrea Parker – Ghost Box Records, The Focus Group, Belbury Poly – The Memory Band – The Delaware Road – Rowan : Morrison – Howlround – Mark Fisher – the BBC Radiophonic Workshop – Adrian Younge’s Electronique Void – DJ Food – Grey Frequency – Keith Seatman – Douglas Powell – Akiha Den Den – The Ghost in the MP3 – Black Channels – The Quietened Village – The Corn Mother

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Now this is a little odd - not only is this here chap trespassing on Hatherley's terrain, he's borrowed his first name too!

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Finally - and no doubt this morsel of news has already reached your flabbergasted ears - but cor blimey guvnor, Paul Weller's only going to release a record on Ghost Box! The In Another Room EP is out early next year. And it's actually rather good.

Moon Wiring Club cometh with his customary seasonal offering: Cavity Slabs. Like the atypical summertime long-player Ghastly Garden Centres of earlier this year, Slabs is a brisk and beat-driven effort, veering away from the boggy hinterland of ambience and vocal gloop into which much of Ian Hodgson's output this past decade has sunk so deliriously. Focused and concise, the new record boasts just eight tuff tunes. The reference point this time around is breakbeat hardcore - in moments, I'm reminded of the phat-but-spooky sound of Eon, although Ian says the launchpad for the new direction was actually this obscure tune:

This very very early Moving Shadow track (by a group later and slightly better known for their Rising High releases) first reached Ian's eardrums via an Autechre radio show from many years ago. "It always stuck with me. It’s that mix of beats with ‘anything goes’ sampling and environmental sounds ~ it always makes me think of coastlines... and a sort of grey mistiness."

The aim with Cavity Slabs was to take a detour round the ongoing overload of rave-replicas, with their neurotic attention to period detail and naked nostalgia, and instead reactivate the bygone playfulness and incongruous-samples-clumsily-collaged approach of the early Nineties, which threw up so many genre-of-one anomalies and half-realised oddments alongside the classic bangers and slammers.

^^^a megamix of three tunes from the album^^^

"I wanted to compose something that reflected the dankness / mystery of fog without it being an ambient drone affair," adds Ian. The name Cavity Slabs comes from a pile of building materials Ian passed on a rainy-day stroll, which conjured associations both of vinyl platters and "limestone moorside and burial chambers". The overall atmosphere and thematic is caught in the slogan "COAX ANCIENT VOICES FROM THE LANDSCAPE" and track titles like "Cromlech Technology" - cromlech being a megalithic altar-tomb or circle of standing stones around a burial mound.

Cavity Slabs is available for purchase here .

But wait... there's more... adding to the Xmas feast, there's a new, radically different version of an old MWC fave: a DL-only VULPINE REDUX edition of Somewhere A Fox Is Getting Married. "The original album plus 47 minutes of 12 bonus track alternate takes / extended versions / tangentially related nonsense from the vaults circa 2006-2011" including unreleased experiments like "35 Year Sit Down" and the lost "Schlagerdelia" classic "Mountain Men".

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Talking of "grey mistiness" - remiss have I been in not alerting parishioners to this new release by Lo Five - Wirral-based electronician Neil Grant.

There's a really nice "mundane mystical" atmosphere to the sound Neil's worked up on his lovely new album Geography of the Abyss - muzzy textures like looking out through a coach window that's streaked with rippling rivulets of heavy rain, or trying to peer through the frosted-glass window of your front door to see who's coming up the path. The vibe of the album reminds me of the sort of trance you can fall into while travelling on a train or a bus, that feeling of slipping outside the moorings of time.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

A record that not only remissly passed without comment from me, but that I missed completely when it originally came out in June - Vanishing Twin's The Age of Immunology.

Triffic stuff - at times like The Focus Group if based around "proper" musicianship rather than sampladelia. As with their previous album Choose Your Own Adventure, the starting points of Broadcast, Stereolab, White Noise, library music, etc, are still discernible, but now they are definitively on a journey of their own.

‘You Are Not an Island’, ‘Invisible World’ and ‘Planete Sauvage’ were apparently "recorded in nighttime sessions in an abandoned mill in Sudbury"!

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

More remissness - alert overdue for the release of the audio element of Andrew Pekler's wonderful Phantom Islands - A Sonic Atlas project of last year.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

A recommendation from parish elder Bruce Levenstein

Release rationale:

Mount Maxwell continues his run of 1970s themed releases with a full length meditation on the perceptual experiences of children born in the wake of the 1960's cultural revolution. Highly ambivalent in tone, Only Children marks a departure from earlier MM releases both in its use of acoustic instruments and in a newfound sense of criticality towards its subject matter; the back-to-the-land optimism of tracks like 'Nature ID' in uneasy proximity to the skeptical disquiet of 'Weird Places' and 'Nomad'.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Bruce also brings to my attention this effort

Release rationale:

There was a certain something about watching television in the 70s and 80s. The static crackle when you switched on your set. The faint smell of ozone as it slowly warmed up. The chunky buttons (including such flights of fancy as 'BBC3' and 'ITV2"). And, of course, the programmes themselves.

Whether it was HTV's seminal Folk Horror tinged children's classics 'Sky' or Children of the Stones, BBC1's fiercely intelligent 'adult-show-for-kids' 'The Changes' or ITV's everyday tale of alien possession, 'Chocky', the era was bursting with inventive, unforgettable and yes, terrifying shows.

The only thing more memorable than the actual programmes were their theme tunes. The unique talents of Paddy Kingsland, Sidney Saget, Eric Wetherell, John Hyde and many more were responsible for the atmospheric, eerie soundscapes which formed the aural backdrop to our favourite shows. Which is where Kev Oyston (The Soulless Party) and Colin Morrison (Castles in Space) come in. They've corralled the best of today's innovative electronic musicians, and together they've created 'Scarred For Life: The Album', a collection of new music inspired by the terrifying televisual sounds of our childhoods.

All proceeds for this album will go to aid Cancer Research UK, a charity which is close to the hearts of some of our artists, one of whom is currently undergoing treatment for cancer.

Enjoy. And remember: DO have nightmares. They're good for you.

-Stephen Brotherstone & Dave Laurence, co-authors 'Scarred For Life Volume One: the 1970's'. .

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

The incredibly prolific and thorough Stephen Prince of A Year in the Country - independent scholar of the rustic eerie and convenor of reliably interesting compilations - has just published a second book.

Straying From the Pathways: Hidden Histories, Echoes of the Future's Past and the Unsettled Landscape is the companion volume to last year's Wandering Through Spectral Fields: Journeys in Otherly Pastoralism, the Further Reaches of Folk and the Parallel Worlds of Hauntology.

How does Stephen do it?!?

More information about Straying From the Pathways here.

Hark at this here Table of Contents!

1. Explorations of an Eerie Landscape: Texte und Töne – The Disruption, The Changes, The Edge is Where the Centre is: David Rudkin and Penda’s Fen: An Archaeology, The Twilight Language of Nigel Kneale, The Stink Still Here – the miners’ strike 1984-85 – Robert Macfarlane – Benjamin Myers’ Under the Rock: The Poetry of a Place

2. Fractured Dream Transmissions and a Collapsing into Ghosts: John Carpenter – Prince of Darkness, Halloween III: Season of the Witch, Village of the Damned, Christine – Nigel Kneale – Martin Quatermass – John Wyndham’s The Midwich Cuckoos

3. Hinterland Tales of Hidden Histories and Unobserved Edgeland Transgressions: Adrian McKinty’s In the Morning I’ll Be Gone – Clare Carson’s Orkney Twilight – David Peace’s GB84 – Tony White’s The Fountain in the Forest

4. Countercultural Archives and Experiments in Temporary Autonomous Zones: Jeremy Sandford and Ron Reid’s Tomorrow’s People – Richard Barnes’ The Sun in the East: Norfolk & Suffolk Fairs – Sam Knee’s Memory of a Free Festival: The Golden Era of the British Underground Festival Scene – Gavin Watson’s Raving ’89 – Molly Macindoe’s Out of Order: The Underground Rave Scene 1997-2006

5. The Village and Seaside Idyll Gone Rogue: Hot Fuzz – The Avengers’ “Murdersville” – The Prisoner – In My Mind – Malcolm Pryce’s Aberystwyth Mon Amour

6. Albion in the Overgrowth and Timeslip Echoes: Requiem – The Living and the Dead – Britannia – Detectorists

7. In Cars – Building a Better Future, Peculiarly Subversive Enchantments and Faded Futuristic Glamour: In the Company of Ghosts: The Poetics of the Motorway – Joe Moran’s On Roads: A Hidden History – Chris Petit’s Radio On – Autophoto – Martin Parr’s Abandoned Morris Minors of the West of Ireland – The Friends of Eddie Coyle – Killing Them Softly – Langdon Clay’s Cars: New York City 1974-76

8. Brutalism, Reaching for the Sky and Bugs in Utopia: Peter Chadwick’s This Brutal World – Bladerunner – J.G.Ballard – Ben Wheatley – High-Rise – Peter Mitchell’s Memento Mori – Brick High-Rise

9. Battles with the Old Guard and the Continuing sparking of Vivid Undercurrents: A Very Peculiar Practice – Edge of Darkness

10. Lycanthropes, Dark Fairy Tales and the Dangers of Wandering off the Path: The Company of Wolves – Danielle Dax – Red Riding Hood – Wolfen – Hansel & Gretel: Witchhunters – The Keep

11. The Empty City Film and Other Visions of the End of Days – Survival and Shopping in the Post-Apocalypse: Day of the Triffids – Into the Forest – Night of the Comet –The Quiet Earth

12. Universe Creation, Spectral Lines in the Cultural Landscape and Reimagined Echoes from the Past: Hauntology – Hypnagogic Pop – Synthwave – D.A.L.I.’s When Haro Met Sally – Nocturne’s Dark Seed – Beyond the Black Rainbow – Mo’ Wax, UNKLE, Tricky, Massive Attack, Portishead, DJ Shadow, Andrea Parker – Ghost Box Records, The Focus Group, Belbury Poly – The Memory Band – The Delaware Road – Rowan : Morrison – Howlround – Mark Fisher – the BBC Radiophonic Workshop – Adrian Younge’s Electronique Void – DJ Food – Grey Frequency – Keith Seatman – Douglas Powell – Akiha Den Den – The Ghost in the MP3 – Black Channels – The Quietened Village – The Corn Mother

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Now this is a little odd - not only is this here chap trespassing on Hatherley's terrain, he's borrowed his first name too!

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Finally - and no doubt this morsel of news has already reached your flabbergasted ears - but cor blimey guvnor, Paul Weller's only going to release a record on Ghost Box! The In Another Room EP is out early next year. And it's actually rather good.

Monday, December 16, 2019

the Future is 50 years old

i.e. young people dancing to electronic music

RIP Gershon Kingsley, who reached the ripe old age of 97

interesting, isn't it, that the Future would emerge first under the sign of easy listening - and even kitsch?

c.f. my "friendly futurists" thesis (Jean-Jacques Perrey et al)

the most successful hit version = Hot Butter

Didn't realise that Jean-Michel Jarre did a version

Makes sense cos "Equinoxe 4" always felt like a semi-rewrite - not literally, but the vibe 'n ' feel, albeit more sedate, less boppy-bouncy

another of the many 'Popcorn' covers

Inane in the Membrane

Thursday, December 5, 2019

Tuesday, November 26, 2019

Neu! versus Alt!

Met Michael Rother last week

Neu!'s children are legion, still

(that last one has a bit of Hawkwind in there, and "Transmission")

Entertaining tunes, but old Neu!s let's be honest

Is it unreasonable for me to not only prefer - but to be biased in favor of - the neu when it was actually neu?

How come alt-Neu! still sounds neu-er than nu-Neu?

The paradox of modernism innit - the Breakthrough, suspended for all time thanks to the 20th Century miracle of recording, recreates the original moment of emergence and insurgence each time you listen (or look, or read). Is somehow eternally new, like fresh-picked fruit flash-frozen.*

Flaubert's Madame Bovary startled me awake, when I read it for the first time last year - even though all its innovations have been long assimilated and rendered second-nature commonplaces in subsequent fiction.

The context for meeting Rother was a Hamburg conference panel discussion in which we were both involved (along with Gudrun Gut, another German modernist albeit of a later vintage) and in which issues of lost futures etc were discussed. Mark Fisher's name came up.

* I also feel that the groups reactivating (if not quite reenacting) the breakthroughs made by other earliers, have evade all the hard work that went into actually breaking through into the new / Neu!. Their undoubted youthful energy masks an idleness - an Idles-ness, even

Neu!'s children are legion, still

(that last one has a bit of Hawkwind in there, and "Transmission")

Entertaining tunes, but old Neu!s let's be honest

Is it unreasonable for me to not only prefer - but to be biased in favor of - the neu when it was actually neu?

How come alt-Neu! still sounds neu-er than nu-Neu?

The paradox of modernism innit - the Breakthrough, suspended for all time thanks to the 20th Century miracle of recording, recreates the original moment of emergence and insurgence each time you listen (or look, or read). Is somehow eternally new, like fresh-picked fruit flash-frozen.*

Flaubert's Madame Bovary startled me awake, when I read it for the first time last year - even though all its innovations have been long assimilated and rendered second-nature commonplaces in subsequent fiction.

The context for meeting Rother was a Hamburg conference panel discussion in which we were both involved (along with Gudrun Gut, another German modernist albeit of a later vintage) and in which issues of lost futures etc were discussed. Mark Fisher's name came up.

* I also feel that the groups reactivating (if not quite reenacting) the breakthroughs made by other earliers, have evade all the hard work that went into actually breaking through into the new / Neu!. Their undoubted youthful energy masks an idleness - an Idles-ness, even

Saturday, November 2, 2019

broken time / brain strain

an article about how the 2010s played havoc with our sense of temporality and strained our brains to breaking point, by Katherine Miller

"This long and wearying decade is coming to a close, though, even if there’s no sense of an ending. People are always saying stuff like: Time has melted; my brain has melted; Donald Trump has melted my brain; I can’t remember if that was two weeks ago or two months ago or two years ago; what a year this week has been. Donald Trump tells the story of 2016 again. Your Facebook feed won’t stop showing you a post from four days ago, about someone you haven’t seen in three years. The Office, six years after it ended, might be the most popular show in the United States. Donald Trump tells the story of 2016 again....

"The touch and taste of the 2010s was nonlinear acceleration: always moving, always faster, but torn this way and that way, pushed forward, and pulled back under....

"In the 20 months between Hillary Clinton’s campaign announcement and Trump’s inauguration, everything from Apple Music to HBO Now to Apple News launched or relaunched; the Amazon Echo, Google Home, and Apple Watch hit the full market; publishers established the current form and tone of the news push alerts that you receive; Facebook launched a livestreaming function and then deprioritized the function when people aired violence; Instagram launched the ephemeral, inexhaustive stories, so you can share — as they put it — “everything in between” the moments you care about; Twitter introduced the quote-tweet option, which formalized and democratized a function from the earlier days of Twitter, and transformed every Trump tweet into an opportunity for commentary.

"And, within a few months in 2016, both the primary catalog for millions of lives (Instagram) and the primary channel for news and culture (Twitter) switched from chronological to algorithmic timelines...."

As well as political churn, Miller also inspects popular culture:

"We’re living through an incredible boom of great shows. Often described, with a weary irony, as the era of Peak TV, this wealth of programming followed tech and traditional premium broadcasters finally figuring out how to commercialize streaming platforms in the 2010s. As a result, you the viewer can move in any sort of direction, watching in bulk something that aired last year, or on Sunday, or one scene again and again, freed from the now-or-never quality that TV once had. For decades, TV either made or ran parallel to the rhythms of American life: morning shows, daytime soaps, the 6 o’clock news, the playoffs, Johnny Carson. In between, the broadcast networks aired 22 half-hour episodes, weekly from September to May, at a fixed time, winding away in sequential order at a mass scale."

Yup, it's not so much that we've lost the monoculture, it's that we've lost monotemporality

Miller quotes Emily Nussbaum on how "time itself has been bent", with one factor being the pause button, which “helped turn television from a flow into text, to be frozen and meditated upon.”

Certainly because it's possible to stop the flow of televisual (or filmic) time, it becomes irresistible to do it at any and every excuse - watching a program or film becomes a stop-start experience with interruptions for urination, rehydration, snacks, unrelated conversational digressions, and then also rewinds to catch dialogue or plot nuances or repeat particularly enjoyable sequences.

Yet it's also likely to be subject to acceleration, with Netflix planning to introduce a 1.5 speed function (and YouTube already allows you to alter the speed of viewing) - which will make watching TV even more fitful and spasmodic.

Long before TV though, I noticed this disruption to the flow of experiential time when I got my first compact disc player in 1989 - with a remote control with pause and skip etc. Music became a frangible, interruptible thing.

Sunday, October 6, 2019

These Reboots Are Made For Watching and That's Just What You'll Do

"Déjà vu may be eerie and unsettling in real life, but on the small screen it’s comfort food. Familiarity breeds content..."

Vanity Fair feature by Joy Press (a.k.a the Missus) on retro-TV - reboots of bygone much-loved series... movie franchise-style prequels and sequels... adaptations from the big screen to the small screen, including zoom-ins that take a second-level character and make them the lead protagonist of a new series.

Vanity Fair feature by Joy Press (a.k.a the Missus) on retro-TV - reboots of bygone much-loved series... movie franchise-style prequels and sequels... adaptations from the big screen to the small screen, including zoom-ins that take a second-level character and make them the lead protagonist of a new series.

Tuesday, September 10, 2019

retro- sexuality (LDR, NFR)

here's my review of Norman Fucking Rockwell!

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

“Watch out Adele! There’s another soul lady coming up behind you and her name is Lana Del Rey.”

So said a Top 40 radio deejay last month, transitioning between “Rolling In the Deep” and “Video Games”. This piece of patter wasn’t just a smart way to introduce an unfamiliar, relatively edgy song to mainstream listeners, it was a rather astute bit of music criticism. Think about it: Adele and Lana Del Rey are young women who’ve had their hearts broken and who sing about it in musical idioms that are overtly non-contemporary: Etta James-style Sixties soul, with Adele, and in Lana Del Rey’s case, something less tightly anchored to specific sources but equally old-timey in its evocations of the Fifties and early Sixties. The question both singers raise is “why do these otherwise thoroughly modern women express first-hand feeling s in such second-hand imagery? Why coat something raw and real in this vintage veneer?”

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

“Watch out Adele! There’s another soul lady coming up behind you and her name is Lana Del Rey.”

So said a Top 40 radio deejay last month, transitioning between “Rolling In the Deep” and “Video Games”. This piece of patter wasn’t just a smart way to introduce an unfamiliar, relatively edgy song to mainstream listeners, it was a rather astute bit of music criticism. Think about it: Adele and Lana Del Rey are young women who’ve had their hearts broken and who sing about it in musical idioms that are overtly non-contemporary: Etta James-style Sixties soul, with Adele, and in Lana Del Rey’s case, something less tightly anchored to specific sources but equally old-timey in its evocations of the Fifties and early Sixties. The question both singers raise is “why do these otherwise thoroughly modern women express first-hand feeling s in such second-hand imagery? Why coat something raw and real in this vintage veneer?”

Lana Del Rey arrived on the scene too recently to make it into my book Retromania, but—like Adele—she is an absolute gift when it comes to talking it up: “look, see, that ’s what I’m on about!” . That said, they represent different kinds of retro-pop. Adele’s is unselfconscious, just an artist who’s embraced a decidedly old-fashioned style and reiterates it without adding much to it.... The hallmark of unselfconscious retro is not dressing the part, not looking like you’ve time-travelled from the era in which the music is sourced.

Lana Del Rey is much closer to the hyper-conscious retro that’s endemic in indie/ underground music, where clothes and artwork reference a bygone era, while the lyrics and the music itself often teem with crafty allusions..... Retro of this kind, where a group’s sound-and-visuals incorporate citations and where spotting them is an integral part of the fan’s enjoyment, is not a new thing. It’s been part of indie almost from the beginning (The Smiths’s iconographic record-sleeves, Jesus & Mary Chain or Butthole Surfers “sampling” riffs or backing vocal refrains from Sixties and Seventies rock legends). It can be traced back further still, through glam rock’s Fifties echoes to The Beatles’s Chuck Berry pastiche “Back In the U.S.S.R.” and Zappa’s doowop album (both 1968). At the same time, there’s no doubt that this kind of conscious retro-activity has intensified in the 21st Century, partly as a result of just how extensive the archive of pop history is now (five or six decades) and partly because the broadband era has made accessing that history so damn easy. YouTube, in particular, is a vast, evergrowing repository of promo and music-on-TV clips along with every other kind of pop (and unpop) culture. And YouTube is as much as audio library as a video archive. You can school yourself there, free of charge.

Which brings us back to Lana Del Rey. Her rocket-like ascent was propelled by videos she put on YouTube made out of footage she’d found on Youtube. “Video Games” and “Blue Jeans” put History in shuffle mode: a miasma of Americana that drifts back and forth across the decades but is unified by its sustained elegiac mood of not-now-ness. Amid the appropriated home movie footage of swimming pools and skateboarders and kids on mopeds, specific allusions pop up: the Hollywood sign, Chateau Marmont, Lana in Lolita sunglasses from Kubrick’s movie, Lana in a racing driver jacket that suggests Evil Knievel or maybe the 70s road movie Two-Lane Blacktop, Lana in a white leather fringe jacket that echoes Easy Rider or maybe Elvis in Las Vegas.

According to Del Rey, though, the recurrent invocations of places like Vegas and LA in her videos (and also her lyrics) aren’t really references so much as mood-tints. “The thing that fascinates me about all of them is the colors of the places,” she says on the phone, in transit to another mythic-Americana landscape she adores, Coney Island. “The muted blues and greens in California, the bright lights of Vegas... People ask me about what the Fifties imagery from California represents to me, but actually I’m mainly just a visual person. Sometimes when my producer and I talk about songs, we talk about them in terms of colors. In a way the album was visually driven. “

Part of the nostalgia effect of the found footage in Del Rey’s videos derives from the properties of the different kinds of film stock, including the specific way that it ages and decays. The bleached and blotchy textures trigger a poignant sense of time’s passage, an inkling that even your most halcyon memories will fade to nothingness. “Blue Jeans” explicitly forefronts the idea of “dead media” and antiquated formats with its opening footage of a hand grabbing a pack of Eastman Ektrachrome Super 8 film.

Lana Del Rey may, in fact, be about to become the first Hipstamatic pop star. Photo apps like Hipstamatic, Instagram, and ShakeIt!, or Fuuvi’s new faux-Super8 device the Bee, offer a digital simulation of an analogue past. Something similar is going on with Lana Del Rey’s music : old-timey instruments like mandolins, strings, harps and twangy surf guitar make up much of its texture, but there’s also unidentifiable sounds flying about that are clearly sampled and processed, while the beats on Born To Die are boombastic, hip hop in impact if not actual feel. The result: the RZA meets Lee Hazelwood. Factor in Del Rey’s choices in clothes, hair, accessories and make-up, and it’s clear she’s the perfect pop star for the era of vintage chic. Not that she’s only artist around with sound-and-visuals that are pre-faded and artificially distressed....

It’s not just the stylized form of Lana Del Ray’s songs that feels out-of-time, it’s the emotional content too: a language of romantic excess that harks back to Roy Orbison’s most over-the-top ballads or Skeeter Davis’s “The End of the World”. Love as malady and madness, delirium and delusion... and at the ultimate degree, death. “Dark Paradise” is a song of morbid fidelity, an abandoned or bereaved lover who prefers to keep the company of ghosts: “There’s no remedy for memory... I wish I was dead.” Elsewhere, Lana sings “I’m not afraid to say that I’d die without him.”

“I don’t really condone relying on another person to the point where you’re going to die without them,” says Del Rey. “Something I never really expected was to have gotten into a relationship that ended up being very tumultuous. But I had met someone who was so magnetic and made me feel differently from the way that I felt for so long, which was sort of confused and bored... and because in the end we couldn’t be together, it ended up having a do-or-die element to it. That was an experience that struck me and I kept on falling back to that place in terms of inspiration for the songs.”

Born To Die goes beyond retro-romance, though, to retro-sexuality, retro-gender. All those yielding, doe-eyed ballads of abject devotion... seem to look back in languor to a time when men were men and women were thankful. A pre-feminist world, or more precisely, America before Betty Friedman’s The Feminine Mystique was published (1963). So in “Without You”, Del Rey coos “I can be your china doll if you want to see me fall”, while “This Is What Makes Us Girls” seems to define femininity as being a fool for love: “We all look for heaven and we put love first/Don’t you know we’d die for it?/ It’s a curse.” At the other extreme, there are songs about women who uses wiles to get what they want. “Off to The Races” recalls Ginger, the Casino character played by Sharon Stone, except if Ginger actually enjoyed being a kept woman and was as docile and adoring as DeNiro’s Sam Rothstein hoped. She’s a moll, wasting a rich man’s money (“give me them coins”), breaking into a Betty Boo squeak for the lines “I’m your little harlot, starlet” and purring “Tell me you own me”.

“I’m an interesting mix of person,” says Del Rey defensively, with just a hint of annoyance. “I am a modern day woman. I’m self-supporting. I went to college. I studied philosophy. I write my own music. But at the same I also very appreciate being in the arms of a man and finding support that way. That feeling influences the kind of melodies I choose and how romantic I make the song. Maybe it ends up giving it a slightly unbalanced feeling.” Asked about the references in other songs on Born To Die about good-girls-gone-bad (“degenerate beauty queens” is one memorable lyric), she points to David Lynch’s movie Wild At Heart as not so much an inspiration as a parallel with phases in her life. “The way I ended up having relationships and living life, it sometimes mimics those more wild relationships. Wild At Heart was an influence – in terms of the way it was shot, but also the love story.”

Right from the off, commentators have talked of Lana Del Rey in terms of David Lynch’s dark dreamworlds. They’ve also mentioned singers linked to his work such as Chris “Wicked Game” Isaak and Julee “Falling” Cruise, whose songs evoke a bygone era when the brokenhearted died inside but did it in style. The Lynch connection highlights a curious quality of Lana Del Rey’s whole shtick: not only does it hark back to the Fifties and early Sixties, it inevitably also recalls the Eighties’s own echoes of that time. Movies like Lynch’s Blue Velvet, Jarmusch’s Strangers in Paradise and Mystery Train, the S.E. Hinton adaptations Rumblefish and The Outsiders. Musicians as various as Tom Waits, Alan Vega, Mazzy Star.

This Sixties-via-Eighties syndrome isn’t unique to del Rey by any means. As much as R&B originals like Etta, Adele recalls forgotten Brit soul revivalists like Alison Moyet, Carmel and Mari Wilson. The scene that Frankie Rose belongs to—Dum Dum Girls, Vivian Girls—reaches Spector’s wall of sound and the Sixties girl group’s via Jesus and Mary Chain and the “C86” movement of bands like The Shop Assistants. Then there’s The Men, as featured in this issue, who draw from the harder side of mid-Eighties British psych-revivalism. On their song “( )” they filch not just the riff from Spacemen 3’s “Revolution” but a chunk of the lyric (“And I suggest to you/That it takes/Just five seconds”) along with lines from another Spacemen song “Take Me To the Other Side”.

If retro culture has reached the point where we’re seeing revivals of revivals, citations of citations (Spacemen 3 remade Stooges songs while “Revolution” itself is an already-somewhat-hokey homage to MC5), what are the implications for music going forward? As time goes on, signs are becoming more and more detached from their historical referents, hollowed out. All these sounds, gestures, time-honored phrases, are entering into a freefloating half-life, or afterlife, where all they are is pure style.

This appears to be the ghosty place where Lana Del Ray comes from. In “Without You”, she sings “but burned into my brain all these stolen images” and I can’t help thinking of Blade Runner and the android replicants who are given transplanted memories. Her lyrics are full of sampled clichés (“ walk on the wild side”, “white lightning”, “feet don’t fail me”) or references to iconic brand-names (“white Pontiac heaven”, “Bugatti Veyron”). But she says that the Pontiac allusion isn’t for its pop-cultural associations (Two Lane Blacktop and other 70s movies, songs by Tom Waits and Jan & Dean) so much as “just the sound” of the word. Likewise, the name “Lana Del Rey” was chosen for its lilting loveliness, rather than its rippling resonances (a Hollywood movie idol with platinum blonde hair and a turbulent private life, a California beach town, a make of 1950s Chevrolet). It was “a big risk” renaming herself, she says, “but my music was always beautiful and I wanted a name that was beautiful too.”

“Beautiful” is a word that crops up repeatedly in Del Rey’s conversation, as it does in her lyrics. She seems to be intensely susceptible to the splendor of appearances, to the point of vulnerability. “You look like a million dollar man/ so why is my heart broke?”, she beseeches plaintively in “Million Dollar Man”. In “National Anthem”, she sings about “blurring the lines between real and the fake.” The gap between image and reality is an obsession. So is fame, portrayed as the dangerous desire to lose oneself by merging into a glamorous facade. “I even think I found god in the flashbulbs of your pretty cameras,” she sings in “Without You”, while the words “Movie Star Without a Cause” flash up in the video for “Blue Jeans”.

Then there’s “Carmen”, seemingly a song about a 17-year-old starlet who’s dying inside and only comes alive when “the camera’s on”, but really more like a perturbing self-portrait. “‘Carmen’ is probably the song closest to my heart,” says Del Rey, who seems vaguely put-out that I’ve heard it. “’Famous and dumb in an early age’—that’s fame in a different way, in different circles, for different reasons. Not really for being a pop star. It’s sort of like, my life”. Once again, you have to wonder about an artistic imagination so colonized by old movies and old songs that it can only express things that really happened in a real life through this “cinematic” prism. Is this a distancing mechanism, a buffer to manage the emotion? Or was the actual love affair itself contaminated by fantasy and role-play?

^^^^^^

What we have with Lana Del Rey is the problem of the undeniable talent who is also a throwback, and who therefore sets back the cause of musical modernism. (See also: The White Stripes). She’s not a straightforward revivalist: the music and the presentation are diversely sourced and the end result is a sophisticated concoction (in that respect, she’s closer to The White Stripes than Adele). But it still falls, ultimately, within the domain of pastiche, memorably defined as “speech in a dead language”. Given her passive persona, it’s tempting to say that the ghosts of pop culture’s collective unconscious speak through her....

[disco edit of Spin, 2012 piece for their Retro-Activity issue]

[full length mix here]

[disco edit of Spin, 2012 piece for their Retro-Activity issue]

[full length mix here]

Tuesday, July 30, 2019

OPM (Other People's Memories), or, The "lucky bag" principle of aleatory record buying applied to photography

aka Why Do Some People Develop the Lost Camera Films of Total Strangers?

Amelia Tait at the Observer, er, observes this strange subculture of hobbyists who purchase rolls of undeveloped film and then develop them - sometimes getting a bunch of blank grey images, sometimes nondescript snapshots, but occasionally something weird or poignant:

"Those who sell mystery film often don’t set out to trade in the stuff, instead it’s usually picked up by chance at house clearances, inside old cameras or in charity shops. There are many tragic reasons why these rolls could have been forgotten about – divorce, death, dementia – and many mundane ones: film processing is expensive and it’s easy to set aside a half-used roll to be finished later and simply forget about it. Used film can sell from £1 to £100 on eBay, and more and more people are gathering online to celebrate their hobby....

"For Levi Bettwieser, a 33-year-old video producer from Idaho, an interest in forgotten film can be both expensive and risky. Bettwieser estimates he has spent “upwards of $10,000” on rolls of film over the past five years, and says he “can get 10 rolls in a row that come out blank” due to the film being degraded. “A couple of years ago, I was winning and buying every single roll of used film on eBay,” Bettwieser says. “There’s always a feeling of overall excitement that you might get something amazing, something historically viable. Or you might get more cat photos.” Bettwieser now runs a non-profit scheme, the Rescued Film Project, where he encourages people to give him their old rolls which he then develops. “Part of the reason I’m doing it is because I like the idea of being the first person to ever see these images; even the photographer has never seen them.”

It's a bit intrusive.... a bit peeping-tom-ish, if you think about it.

It's also archive fever finding a new zone to flex itself in - again the idea that everything deserves to be preserved....

“I love so many images for so many reasons,” says Bettwieser, when asked about his favourite photo he’s recovered. “I try and look at every image I rescue as if I’m looking at it in 50 years – everything I rescue is history. People hold on to rolls of film for years and years in the back of a drawer, because we all know that pictures are history, whether it’s just a birthday party or not. Pictures are our only defence against time, our only evidence, sometimes, that we ever even existed.”

Postscript August 1st -

interesting thoughts on this subject from Xenogothic, who is a collector of such images and is drawn to them for their "alterity"-

"The main thrill comes from seeing something radically out of context. The anxiety of the unanswerable question that haunted Roland Barthes instead becomes a perverse thrill — indeed, as it was for Barthes though he seemed reluctant to admit it.

Like an object found on the beach in a ghost story, the energy trapped in a photograph like a fly in amber is a special thing that is highly susceptible to romantic flights of the nostalgic subject and, as such, to find such things in the world of the vernacular image is far past the pale of cliche...."

Xenogothic also says that another place to find such images is record covers

Amelia Tait at the Observer, er, observes this strange subculture of hobbyists who purchase rolls of undeveloped film and then develop them - sometimes getting a bunch of blank grey images, sometimes nondescript snapshots, but occasionally something weird or poignant:

"Those who sell mystery film often don’t set out to trade in the stuff, instead it’s usually picked up by chance at house clearances, inside old cameras or in charity shops. There are many tragic reasons why these rolls could have been forgotten about – divorce, death, dementia – and many mundane ones: film processing is expensive and it’s easy to set aside a half-used roll to be finished later and simply forget about it. Used film can sell from £1 to £100 on eBay, and more and more people are gathering online to celebrate their hobby....

"For Levi Bettwieser, a 33-year-old video producer from Idaho, an interest in forgotten film can be both expensive and risky. Bettwieser estimates he has spent “upwards of $10,000” on rolls of film over the past five years, and says he “can get 10 rolls in a row that come out blank” due to the film being degraded. “A couple of years ago, I was winning and buying every single roll of used film on eBay,” Bettwieser says. “There’s always a feeling of overall excitement that you might get something amazing, something historically viable. Or you might get more cat photos.” Bettwieser now runs a non-profit scheme, the Rescued Film Project, where he encourages people to give him their old rolls which he then develops. “Part of the reason I’m doing it is because I like the idea of being the first person to ever see these images; even the photographer has never seen them.”

It's a bit intrusive.... a bit peeping-tom-ish, if you think about it.

It's also archive fever finding a new zone to flex itself in - again the idea that everything deserves to be preserved....

“I love so many images for so many reasons,” says Bettwieser, when asked about his favourite photo he’s recovered. “I try and look at every image I rescue as if I’m looking at it in 50 years – everything I rescue is history. People hold on to rolls of film for years and years in the back of a drawer, because we all know that pictures are history, whether it’s just a birthday party or not. Pictures are our only defence against time, our only evidence, sometimes, that we ever even existed.”

Postscript August 1st -

interesting thoughts on this subject from Xenogothic, who is a collector of such images and is drawn to them for their "alterity"-

"The main thrill comes from seeing something radically out of context. The anxiety of the unanswerable question that haunted Roland Barthes instead becomes a perverse thrill — indeed, as it was for Barthes though he seemed reluctant to admit it.

Like an object found on the beach in a ghost story, the energy trapped in a photograph like a fly in amber is a special thing that is highly susceptible to romantic flights of the nostalgic subject and, as such, to find such things in the world of the vernacular image is far past the pale of cliche...."

Xenogothic also says that another place to find such images is record covers

Saturday, June 1, 2019

dead pop stars and their profitable afterlife

Interesting piece on the pop hologram phenomenon by Owen Myers at The Guardian, featuring some quotes from me, specifically on the exploitation of dead stars .

In response to a question about whether watching a hologram performance was really any different from watching, say, an old Marilyn Monroe

movie on TV.... .

Here's the full responses I sent to Owen a week or two ago:

My gut insta-reaction is that it’s a new

way for the old to tyrannize the young – because you can’t get any older than

being dead. So the next step beyond the reunion tours, and all the legacy acts

that dominate festival line-ups, is the hologram tour: no longer alive artists

extending their brand power beyond the grave.

The syndrome raises all kinds of ethical

and philosophical questions. To what extent are these performances in

any real sense, given that a performance (whether showbiz entertainment or performance

art) is by definition live, involving the unmediated presence of living

performers, whereas the hologram tours are “unlive” and involve

non-presence?

On an ethical and economic level, I would liken

it to a form of “ghost slavery”. That applies certainly when done without the

consent of the star, by the artist’s estate in collusion with the record

company or tour promoter.

But even if an artist might consent while still alive

and legally grant the posthumous rights to their image, voice, etc, for

exploitation, that doesn’t make it right or proper. Nor does the fact that

there might be a consumer demand for this make it a wholesome development.

It’s a

form of unfair competition: established stars continuing their market

domination after their death and stifling the opportunities for new artists.

It’s reminiscent of Marx on capital as the spectral vampire of dead labour, which when living and working had surplus value sucked out of it and then turned into yet more finance capital, thereby continuing the dominion over and exploitation of living

labour for generations to come. But it’s Das Kapital crossed with Freud’s writings about the uncanny.

Hologram tours are very much an extension

of the syndromes discussed in Retromania. I don’t think they existed as more

than a rumour when I was writing the book - there might be a brief mention of

them in there. But I do discuss the idea of movie stars being reanimated and

how that was happening then already with figures like Audrey Hepburn being used in

commercials using digital trickery.

It does seem like another facet to

this that will soon be possible is that the technology will emerge such that the vocal timbre and mannerisms, the

facial expressions and bodily gestures, conversational speech patterns, etc etc, of performers can be captured

digitally - through assimilating and analysing the sum total of all their existing recordings, performances, videos, films, etc etc - and that you will get a sort of digi-simulacrum of the artist

singing new songs, guesting as vocalist or rapper on other people’s records,

appear in videos or movies etc. That seems totally conceivable to me. The

simulacrum would probably not be able to do convincing spontaneous stage banter

or appear on chat shows, but who knows? In those circumstances, they

could be remotely ventriloquized by someone offstage, so that that person’s

voice – or even written text – would be spoken by the simulacrum’s real-seeming

voice. In the recording studio, you’d just need the software which would

generate the voice, or the instrumental performance.

No, I think there’s a greater dimension

of wish-fulfillment and suspension of disbelief. The spectators are allowing

themselves to half-believe that they are in the presence of the star. That’s

why it’s like a ghost – a ghost could be defined as a “present absence”,

neither here nor there, neither now nor then, but in some ontologically queasy

interzone between being and nonbeing.

It’s eerie, it’s fascinating, it’s

troubling.

Thursday, May 23, 2019

superzero

“This embracing of what were unambiguously

children's characters at their mid-20th century inception seems to indicate a

retreat from the admittedly overwhelming complexities of modern existence... It

looks to me very much like a significant section of the public, having given up

on attempting to understand the reality they are actually living in, have

instead reasoned that they might at least be able to comprehend the sprawling,

meaningless, but at-least-still-finite 'universes' presented by DC or Marvel

Comics. I would also observe that it is, potentially, culturally catastrophic to

have the ephemera of a previous century squatting possessively on the cultural

stage and refusing to allow this surely unprecedented era to develop a culture

of its own, relevant and sufficient to its times" - Alan Moore

I guess there is a retro element to the endless torrent of Marvel / DC / et al superhero vehicles

A regressive or stagnant element in terms of character typology, motivation, fantasy, morality, narrative etc

Coupled - paradoxically - with absolutely ultra-modern state of the art powers being flexed in terms of the technical execution of these "children's entertainments" - the CGI and motion-capture, the 3-D camerawork, the sound design, the grading, the editing etc etc etc.

A parallel to my avant-lumpen theory about the most progressive or futuroid musical forms being coupled with politically regressive values and attitudes.

Technosonically in the future; emotionally-libidinally in the.... Middle Ages, really.

Codes of honor, warrior-masculinity, potlatch etc etc

Return of the saga, the legend, the epic, the allegorical etc etc

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

On the subject of heroics and heroism, I think also of this book

I guess there is a retro element to the endless torrent of Marvel / DC / et al superhero vehicles

A regressive or stagnant element in terms of character typology, motivation, fantasy, morality, narrative etc

Coupled - paradoxically - with absolutely ultra-modern state of the art powers being flexed in terms of the technical execution of these "children's entertainments" - the CGI and motion-capture, the 3-D camerawork, the sound design, the grading, the editing etc etc etc.

A parallel to my avant-lumpen theory about the most progressive or futuroid musical forms being coupled with politically regressive values and attitudes.

Technosonically in the future; emotionally-libidinally in the.... Middle Ages, really.

Codes of honor, warrior-masculinity, potlatch etc etc

Return of the saga, the legend, the epic, the allegorical etc etc

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

On the subject of heroics and heroism, I think also of this book

Friday, May 17, 2019

Hauntology Parish Newsletter spring 2019 - Moon Wiring Club, Baron Mordant, The Caretaker

In the new edition of The Wire, I have an extended essay-review about the career-closing releases from The Caretaker and Mordant Music: the sixth and final installment of James Kirby's gargantuan Everywhere at the end of Time project, which started three years ago, and Baron Mordant's last blast, Mark of the Mould. The latter is an unmissable emission - like eMMplekz if the Baron handled the backing tracks as well as the verbals... the latter proving once again that Ian Hicks is simultaneously the Robert Macfarlane of built-up Britain and the Chris Morris of BoomkatKultur.

Also ruffling the parish this month - and making this newsletter a tale of two Ians - is the announcement of an unexpected, non-wintertime release from Moon Wiring Club aka Ian Hodgson.

Ghastly Garden Centres is a timely swerve from the ambient-amorphous direction of recent MWC releases and a jaunty step into brisk concision. In fact, the guiding concept here is that every track is a single - making the assemblage perhaps a Now! style compilation of hits, or a chart countdown. It's MWC - so it's still creepy and manky - but it's also catchy and bouncy.

As for the ghostly-ghastly gardening theme - well, apparently this is a real thing, a subject of internet obsession: abandoned, overgrown plant nurseries and derelict garden centres.

Further raising the pulse of parishioners is the parallel release of Catmask, a collection - styled as issue no. 1 of a glossy magazine - that pulls together Ian Hodgson's artwork: some already released, on the records or at the Blank Workshop website, but much unfamiliar and never seen. There are images from Ian's abandoned children's book project, for instance, which if I recall correctly, was the acorn from which grew the mighty oak of Clinkskell and the 21 - or 23, depending on how you count - releases to date, including collaborations and side projects.

Catmask is a gorgeous slinky looking and feeling object to peruse and fondle. It completes the sense of Moon Wiring Club as a project of.... I won't say, world-building, as that's a cliche now... but place-making, maybe.

UK customers can buy Ghastly Garden Centres and Catmask here

European customers can buy Ghastly Garden Centres and Catmask here

Rest of world customers can buy Ghastly Garden Centres and Catmask here

Also ruffling the parish this month - and making this newsletter a tale of two Ians - is the announcement of an unexpected, non-wintertime release from Moon Wiring Club aka Ian Hodgson.

Ghastly Garden Centres is a timely swerve from the ambient-amorphous direction of recent MWC releases and a jaunty step into brisk concision. In fact, the guiding concept here is that every track is a single - making the assemblage perhaps a Now! style compilation of hits, or a chart countdown. It's MWC - so it's still creepy and manky - but it's also catchy and bouncy.

As for the ghostly-ghastly gardening theme - well, apparently this is a real thing, a subject of internet obsession: abandoned, overgrown plant nurseries and derelict garden centres.

Further raising the pulse of parishioners is the parallel release of Catmask, a collection - styled as issue no. 1 of a glossy magazine - that pulls together Ian Hodgson's artwork: some already released, on the records or at the Blank Workshop website, but much unfamiliar and never seen. There are images from Ian's abandoned children's book project, for instance, which if I recall correctly, was the acorn from which grew the mighty oak of Clinkskell and the 21 - or 23, depending on how you count - releases to date, including collaborations and side projects.

Catmask is a gorgeous slinky looking and feeling object to peruse and fondle. It completes the sense of Moon Wiring Club as a project of.... I won't say, world-building, as that's a cliche now... but place-making, maybe.

UK customers can buy Ghastly Garden Centres and Catmask here

European customers can buy Ghastly Garden Centres and Catmask here

Rest of world customers can buy Ghastly Garden Centres and Catmask here

Thursday, May 9, 2019

meat(loaf) substitute

Tim Somner notices that

"Meat Loaf has, essentially, given his name and brand good-will to another artist, who is, essentially, touring as Meat Loaf . Personally, I think this is the wave of the future"

Yes, this is one step further towards rock developing the equivalent of classical music repertory

But it's not just the score / songs that has to be reconstituted - it's the voice and the performance moves, the presence of the performer, as ersatz

Rock being as much about the vocal personality and the look / vibe of the artist, as it is about notes and textures and tempos.

The facsimile artist must replicate as closely as possible the grain of the singer's voice, the phrasing, the staging and gestures - all of those elements are "the score"

There was a Genesis tribute band who did a whole tour based on the The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway Tour and got hold of the original slide projections and other staging elements (costumes, i should imagine) from Genesis. The whole thing was done with their blessing and perhaps with some of the revenue going to the original band, who knows.

You could imagine a really big band that is too old or frail to tour anymore actually franchising out concert-playing versions of themselves in different territories - South America, Asia, Eastern Europe / Russia.

Of course the other route for retro-rock nostalgia would be the hologram tour, when it's a ghostly simulacrum of the artist as was that is wheeled out to "tread the boards"

But it's not too hard to imagine that digital technology could soon be capable of turning an artist's whole being - the sound, the look, the mannerisms, even creative reflexes - into an immortal brand that carries on long after the artist's death, perhaps even creating and performing new songs. Generating a revenue stream for the estate on top of the publishing, recording, etc monies. T

You could imagine that being done fairly easily with an actor, or a singer... motion-capturing all the facial expressions and vocal / conversational tics - and then perhaps pasting that stuff on top of a body double in the filming situation, or simply generating it artificially for recordings.

The creative part - and the side that can do interviews or on-stage spontaneous banter, or collaborate with other musicians, jamming onstage with them or writing songs - that might be a little harder. But given how fast technology has advanced, it's fairly likely that within our lifetime we'll see technology that can capture the soul-signature of an artist's identity and turn it into generative software.

A new way that the dead can tyrannise the living, the old dominate the young.

"Meat Loaf has, essentially, given his name and brand good-will to another artist, who is, essentially, touring as Meat Loaf . Personally, I think this is the wave of the future"

Yes, this is one step further towards rock developing the equivalent of classical music repertory

But it's not just the score / songs that has to be reconstituted - it's the voice and the performance moves, the presence of the performer, as ersatz

Rock being as much about the vocal personality and the look / vibe of the artist, as it is about notes and textures and tempos.

The facsimile artist must replicate as closely as possible the grain of the singer's voice, the phrasing, the staging and gestures - all of those elements are "the score"

There was a Genesis tribute band who did a whole tour based on the The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway Tour and got hold of the original slide projections and other staging elements (costumes, i should imagine) from Genesis. The whole thing was done with their blessing and perhaps with some of the revenue going to the original band, who knows.

You could imagine a really big band that is too old or frail to tour anymore actually franchising out concert-playing versions of themselves in different territories - South America, Asia, Eastern Europe / Russia.

Of course the other route for retro-rock nostalgia would be the hologram tour, when it's a ghostly simulacrum of the artist as was that is wheeled out to "tread the boards"

But it's not too hard to imagine that digital technology could soon be capable of turning an artist's whole being - the sound, the look, the mannerisms, even creative reflexes - into an immortal brand that carries on long after the artist's death, perhaps even creating and performing new songs. Generating a revenue stream for the estate on top of the publishing, recording, etc monies. T

You could imagine that being done fairly easily with an actor, or a singer... motion-capturing all the facial expressions and vocal / conversational tics - and then perhaps pasting that stuff on top of a body double in the filming situation, or simply generating it artificially for recordings.

The creative part - and the side that can do interviews or on-stage spontaneous banter, or collaborate with other musicians, jamming onstage with them or writing songs - that might be a little harder. But given how fast technology has advanced, it's fairly likely that within our lifetime we'll see technology that can capture the soul-signature of an artist's identity and turn it into generative software.

A new way that the dead can tyrannise the living, the old dominate the young.

Friday, May 3, 2019

ArchivFieber, slight return - "The Remarkable Story of a Woman Who Preserved Over 30 Years of TV History"

via Atlas Obscura

"About 71,000 VHS and BETAMAX cassettes are sitting in boxes, stacked 50-to-a-pallet in the Internet Archive’s physical storage facility in Richmond, California, waiting to be digitized. The tapes are not in chronological order, or really any order at all. They got a little jumbled as they were transferred. First recorded in Marion Stokes’s home in the Barclay Condominiums in Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia, the tapes had been distributed among nine additional apartments she purchased solely for storage purposes during her life. Later, they passed on to her children, into storage, and finally to the California-based archive. Although no one knew it at the time, the recordings Stokes made from 1975 until her death in 2012 are the only comprehensive collection preserving this period in television media history.

"In 1975, Stokes got a Betamax magnetic videotape recorder and began recording bits of sitcoms, science documentaries, and political news coverage. From the outset of the Iran Hostage Crisis on November 4, 1979, “she hit record and she never stopped,” said her son Michael Metelits in Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project, a newly released documentary about his mother and the archival project that became her life’s work."

"Stokes was no stranger to television and its role in molding public opinion. An activist archivist, she had been a librarian with the Free Library of Philadelphia for nearly 20 years before being fired in the early 1960s, likely for her work as a Communist party organizer...."

"Roger Macdonald, director of the television archives at the Internet Archive.... recalls asking [Michael] Metelits, “How could you physically manage taping all this stuff? And he said, ‘Well, we’d be out at dinner and we’d have to rush home to swap tapes’ … that was one of the cycles of their lives, tape swapping.”

"In addition to her son Michael and her husband, Stokes’s nurse, secretary, driver, and step-children were enlisted to assist in her around-the-clock task of capturing every moment on television....

"Now, Stokes’s work will be made publicly available on the Internet Archives, bit by bit, offering everyone the opportunity to examine history..."

Calling Borges, or do I mean Benjamin....

"About 71,000 VHS and BETAMAX cassettes are sitting in boxes, stacked 50-to-a-pallet in the Internet Archive’s physical storage facility in Richmond, California, waiting to be digitized. The tapes are not in chronological order, or really any order at all. They got a little jumbled as they were transferred. First recorded in Marion Stokes’s home in the Barclay Condominiums in Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia, the tapes had been distributed among nine additional apartments she purchased solely for storage purposes during her life. Later, they passed on to her children, into storage, and finally to the California-based archive. Although no one knew it at the time, the recordings Stokes made from 1975 until her death in 2012 are the only comprehensive collection preserving this period in television media history.

"In 1975, Stokes got a Betamax magnetic videotape recorder and began recording bits of sitcoms, science documentaries, and political news coverage. From the outset of the Iran Hostage Crisis on November 4, 1979, “she hit record and she never stopped,” said her son Michael Metelits in Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project, a newly released documentary about his mother and the archival project that became her life’s work."

"Stokes was no stranger to television and its role in molding public opinion. An activist archivist, she had been a librarian with the Free Library of Philadelphia for nearly 20 years before being fired in the early 1960s, likely for her work as a Communist party organizer...."

"Roger Macdonald, director of the television archives at the Internet Archive.... recalls asking [Michael] Metelits, “How could you physically manage taping all this stuff? And he said, ‘Well, we’d be out at dinner and we’d have to rush home to swap tapes’ … that was one of the cycles of their lives, tape swapping.”

"In addition to her son Michael and her husband, Stokes’s nurse, secretary, driver, and step-children were enlisted to assist in her around-the-clock task of capturing every moment on television....

"Now, Stokes’s work will be made publicly available on the Internet Archives, bit by bit, offering everyone the opportunity to examine history..."

Calling Borges, or do I mean Benjamin....

Wednesday, April 24, 2019

the horror, the horror

A piece at Loud and Quiet looking back on The Horrors's second album Primary Colours, ten years after the fact.

Writes Fergal Kinney:

"Of course, British bands have been referencing the electronic utopia of Krautrock since the late ’70s, but the internet afforded those records an ease of access which had always been absent – former collectors items are now just a click and an aux cable away. Simon Reynolds’ post-punk study Rip It Up and Start Again was read within the band too. “Just reading that book gives you ideas for ten different bands,” says Faris [Badwan]. “That book was really influential for me.”"

Well, I'm flattered, naturally - but talk about getting the wrong end of the stick!

The point you should come away with, from reading Rip It Up, is obviously (or so I thought) "do something new!". That might mean "do something that's a warped and strange-making take on the new ideas bubbling out of your contemporaneous musical surroundings" (generally black music, so at that time, second half of the 2000s, grime, nu-R&B, dubstep). Or it might mean "do something that involves the latest technology" e.g. Auto-Tune, etc etc).

The "instruction" to come away from reading that book would be "apply the methods and outlook and mentality and procedures that created the legendary music". Expressly not "reactivate the actual substance of the legendary music; repeat the exact same hybridizing formulas that led to it, or recreate the outcomes of those musical equations."

Still, it's a good inadvertent illustration of the connection between Retromania and Rip It Up (and indeed between both those books and Energy Flash - the three forming an unintended triology, as my Faber editor Lee Brackstone once put it). It explains how doing Rip It Up led directly to Retromania (indeed Rip's afterword contains a section on the "rift of retro" that occurred in alternative / independent rock circa 1983-84, effectively ending the postpunk era.)

Further, it demonstrates how the person who wrote Rip It Up, who had lived through and felt in their fibres the meaning of that era the first time around and then relived it as an immersed historian, could only respond to the 2000s (the first decade of the 21st bleedin' century) with the perspective that underpins Retromania.

And the post-punk revival - although far from alone as evidence for prosecution - was exactly the kind of contradiction-in-terms that spurred the book into being.

Writes Fergal Kinney:

"Of course, British bands have been referencing the electronic utopia of Krautrock since the late ’70s, but the internet afforded those records an ease of access which had always been absent – former collectors items are now just a click and an aux cable away. Simon Reynolds’ post-punk study Rip It Up and Start Again was read within the band too. “Just reading that book gives you ideas for ten different bands,” says Faris [Badwan]. “That book was really influential for me.”"

Well, I'm flattered, naturally - but talk about getting the wrong end of the stick!

The point you should come away with, from reading Rip It Up, is obviously (or so I thought) "do something new!". That might mean "do something that's a warped and strange-making take on the new ideas bubbling out of your contemporaneous musical surroundings" (generally black music, so at that time, second half of the 2000s, grime, nu-R&B, dubstep). Or it might mean "do something that involves the latest technology" e.g. Auto-Tune, etc etc).

The "instruction" to come away from reading that book would be "apply the methods and outlook and mentality and procedures that created the legendary music". Expressly not "reactivate the actual substance of the legendary music; repeat the exact same hybridizing formulas that led to it, or recreate the outcomes of those musical equations."

Still, it's a good inadvertent illustration of the connection between Retromania and Rip It Up (and indeed between both those books and Energy Flash - the three forming an unintended triology, as my Faber editor Lee Brackstone once put it). It explains how doing Rip It Up led directly to Retromania (indeed Rip's afterword contains a section on the "rift of retro" that occurred in alternative / independent rock circa 1983-84, effectively ending the postpunk era.)

Further, it demonstrates how the person who wrote Rip It Up, who had lived through and felt in their fibres the meaning of that era the first time around and then relived it as an immersed historian, could only respond to the 2000s (the first decade of the 21st bleedin' century) with the perspective that underpins Retromania.

And the post-punk revival - although far from alone as evidence for prosecution - was exactly the kind of contradiction-in-terms that spurred the book into being.

Thursday, April 11, 2019

nostalgia for the future / militant modernism

Here's something I really enjoyed researching and writing - a feature for RBMA on Luigi Nono, the great "militant modernist" of post-WW2 avant-garde music. This article focuses on his electronic and tape works of the 1960s, his exploration of vocal extremes, his support for liberation movements around the world, and the surrounding context of Italian Communism in the post-war era.