[adapted from a talk delivered at the conference Aesthetics of Steampunk at the Universita di Bologna in June 2022]

My subject today is steampunk as a subgenre – or side-genre - of alternative history. Which is itself a subgenre – or side-genre – of science fiction. I'll be exploring how those three interconnected genres of speculative fiction might have a relationship with hauntology – understood here as both the philosophical idea originated by Derrida, but also hauntology as a somewhat nebulous genre of music. That hauntology is a current of ideas about sound and memory that you can trace back to the end of the 20th Century with groups like Boards of Canada and Broadcast but that really took shapeless shape in the first decade of the 21st Century, when Mark Fisher and I together started using the term hauntology around 2005, to describe mostly British artists like Burial, The Caretaker, the Ghost Box label (The Focus Group, Belbury Poly, the Advisory Circle, et al), Mordant Music, Moon Wiring Club, along with a few Americans, such as William Basinski and Ariel Pink's Haunted Graffiti.

Alternative history has other names: counterfactuals, uchronia (a term that merges utopia, which literally means no-place, and time, via chronos), allohistory, alternate history. But whatever the term you prefer, this is a mode of science fiction that imagines the different route that History could have taken, resulting in radically different realities to the one we inhabit.

Right away, you can see there's an affinity here between alternative history and hauntology. Hauntology, in both the philosophical and musical senses, is concerned with the spectral traces of “lost futures” that persist and linger on the cultural landscape: dreams of tomorrows that never came but haunt and taunt us with their betrayed promise. Alternative history is about the ghosts – the mirages – of other presents; distorted reflections of our world. It uses the same speculative fiction techniques as science fiction, but instead of projecting forwards, it projects sideways through time– to versions of the present where history took a different path, usually because of a specific turning point that in this fictional scenario turned the other way.

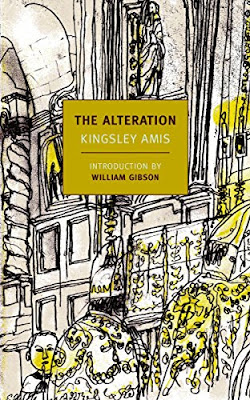

Alternative history fetishizes the notion of the Event, the turning point; it revels in the look and feel of worlds based around differently evolved technology; it takes delight in in ironies, reversals, and displacements. So often real life historical characters in our history reappear in incongruous places. In Ward Moore's Bring the Jubilee, a contender for Greatest Alternative History novel ever, Carl Jung is a Swiss police chief who specializes in the study of criminals by the shape of their heads. In Kingsley Amis's The Alteration, a world where the Reformation was defeated and Roman Catholicism rules almost supreme, Harold Wilson - in our reality the Labour prime minister - is a pipe-smoking Pope.

But although there is humor, there is also estrangement, a making-strange, at work in alternative history. The effect on the reader of alternative history and the best steampunk writing is similar to how listeners experience hauntological music. There are other aesthetic traits in common: a love of clunky hardware, quaint and cumbersome technology that is heavy and takes up a lot of space, but is somehow still futuristic, just like analogue modular synths. There’s also similar blends of moods: whimsy, horror, the macabre, the grotesque, the eerie, all jumbled up together.

The title for this talk - Sideways Through Time – comes from a lyric from Hawkwind’s “Silver Machine”, Hawkwind are the British Underground kings of space rock of the 1970s, and they're a rock band overtly influenced by science fiction. They collaborated in fact with the science fiction and fantasy writer Michael Moorcock, who will appear later as an ancestor of steampunk. The lyric mentions how the silver spacecraft “flies sideways through time”, but I have always heard it as “slides” - sometimes “glides” - and I'm sticking with that poetic-feeling mishearing.

Here's a funny thing: when I picked that as my title I was completely unaware that one of the foundations of the alternative history genre in s.f. is Murray Leinster’s short story “Sidewise In Time”, published in 1934. Sidewise is an alternative way of saying sideways – it’s slightly archaic. Leinster’s story belongs to a particular kind of alternative history involving the idea of parallel universes: the "sidewise" is when someone slips - or slides - across into a different universe, where causality went differently.

Separate from science fiction, there

is a form of alternative history that is a kind of parlour game for actual historians. They write

historical essays on different scenarios – like, what if Napoleon had won at

Waterloo, or escaped from Elba. Many historians look down on this as an

unserious activity. But I do remember one of my tutors at university bringing

up a counterfactual possibility – we were studying the Austro-Hungarian Empire

and he said, what do you think of the idea that it would have better if the

Empire had stayed together and gradually evolved into a confederation of Balkan

states. A sort of Eastern European Community.

For the most part, though, alternative history is a field that has been largely left to fiction writers. The more interesting examples of the form are those that use the same methodology as the near-future science fiction story. Not science fiction of the sort that's set millions of years into the future, and that involves interstellar empires and alien races. Rather, this near-future science fiction involves using the historical method speculatively; it projects forward into plausible scenarios based on current trends and chains of causality.

Alternative history uses the same techniques but its start point is located further back in the past – it locates a turning point, a fork in the path of time where instead of going right (towards the historical reality we live in) it goes left. Bend sinister. The turning point is often a battle, a military victory that is reversed. Or an assassination or the unscheduled early death of a key figure, or the survival of a key figure who died early in our reality. It could be the premature invention of a technology, as with the definitive steampunk novel, William Gibson and Bruce Sterling’s The Difference Engine, where Babbage succeeds in making a functioning computer more than a century ahead of schedule.

Not long before starting collaborative work on The Difference Engine, Gibson explored ideas of a different kind of retrofuturism in his famous story “The Gernsback Continuum”. The title nods to Hugo Gernsback, who in 1926 founded the s.f. magazine Amazing Stories. One character in Gibson’s story talks about 'semiotic ghosts' - culturally persistent after-images of yesterday's visions of tomorrow generated by the collective unconscious - but to the central character this feels like a hallucinatory affliction, like bleed-throughs from a parallel present, a world where the dreams of 1930s science fiction and the World Fairs of that time came true – as Gibson writes, a "kind of alternate America...A 1980 that never happened, an architecture of broken dreams”, 'American Streamlined Moderne'. For Gibson, his story was a critique of the cult of technology, the belief that progress is an inevitable byproduct of technological advances.

Bruce Sterling, the coauthor of The

Difference Engine, around about this time started the Dead Media Project, for the cataloguing of examples of outmoded technology. This was the crystallization of a new sensibility of

retrofuturism, and one that is very close to hauntology. There's an exquisitely heightened sensitivity to the pathos and

weirdness of machinery that was very recently cutting edge but is now antique. Although obsolete, these machines seem to contain a trapped promise of futurity, a foreclosed path into the future that could have been. Again, emotionally and aesthetically, this is close to hauntology and to related genres like vaporwave.

The Difference Engine codified steampunk

as a distinct subgenre of alternate history, as well as a kind of sideways

offshoot of cyberpunk. But intriguingly, steam power crops up in a number of alternative

history novels that preexisted the notion of steampunk. Alongside the Victorian / Edwardian aesthetic, you also find such staples of the genre as the airship, the

lighter than air balloon that carries freight or passengers. The dirigible, to

use an old fashioned word, which means a balloon that can be steered and propelled

by a motor, rather than just carried by the wind.

Dirigible airships feature in Michael

Moorcock's The Warlord of the Air – the first of his trilogy A Nomad of

the Time Streams, alongside The Land Leviathan and The Steel Tsar. Where as an adolescent I planned

to write about a world where Germany won the First World War, here the First

World War never happened at all – Edwardian manners and style prevail and the

European empires still rule the world.

Dirigibles also appear in Ward Moore’s

Bring the Jubilee (1955), which involves a world where the Confederate South won the Civil

War. Another technological side-effect in Moore's brilliant imagining is that the combustion engine is never

invented. Instead there is a vehicle called a minibile – a small, trackless

locomotive powered by steam, similar to what in our world was called the

traction engine. In Bring the Jubilee, the minibile is something

only the wealthy can afford, partly because of its size and also because it

requires a trained driver to operate.

Pavane by Keith Roberts, written as separate short stories and then combined as a novel in 1966, describes a world where Elizabeth the First was assassinated, the Spanish Armada successfully conquered England , and as a result the Reformation is crushed and Roman Catholicism is triumphant. In the 20th Century of Pavane, science is tightly controlled by the Church, electricity forbidden, so there's no internal combustion engine here either. Instead, personal cars are powered by wind sails and for heavier transportation there is steam power: heavy goods are carried by ‘road trains,’ steam locomotives that don’t run on tracks but pull behind them wagons loaded with goods. The first story in the book involves a haulier making the dangerous journey through the wilderness of the Southern England province of Dorset. He's in danger of attack from routiers, gangs of bandits on horses. So it's a bit like the Wild West in America around 1890, but transposed into a late 20th Century largely rural England that is still Medieval, in which barons live in castles (Corfe Castle is still inhabited) and the Inquisition is busily torturing witches and the possessed.

A similar scenario – a Catholic England where science is suppressed – is the backdrop to Kingsley Amis’s The Alteration (1976). William Gibson wrote the introduction to a new edition of the book published in the early 21st Century, and offered this high praise:

“I must recommend it as containing the single finest steampunk set piece I know of: a seven-hour luxury train journey between London and Rome, via Sopwith’s magnificent Channel Bridge.”

Steam – and alternative technology – don’t play a large role in Amis book. But one thing he does do, in a homage to Philip K. Dick’s classic counterfactual The Man In the High Castle, is to feature a book within the book. Teenage boys in this altered world surreptitiously read a scandalous fiction in clandestine circulation because it imagines something equivalent to our world – where the Reformation happened and science flourished.

Amis goes one better than Dick, though – he imagines a completely different genre. Because ‘science’ is a bad word in this world, the genre is called Time Romance. Romance, here meaning ‘novel’ as in the Italian romanzo or the French roman. And there is also a subgenre of Time Romance that is equivalent to alternative history – it’s called Counterfeit World. So in other words, a fake reality, a false history.

The closest to the steampunk aesthetic that I’ve found in an alternate history novel that predates The Difference Engine is Harry Harrison’s A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hooray!, which was published in 1972. Here the scenario is a world where the British Empire still rules all of North America. The technology is not exactly steampunk: there are no airships, but instead heavier than air airplanes are fueled by the burning of pulverized coal - by coal dust. And although we see a formidable steam train that can travel at 200 miles per hour it turns out that the steam is heated by a small nuclear reactor in the locomotive engine! What really makes the novel steampunk is the overall aesthetic of the world – the look, the manners, the social structure. Harrison wrote that when conceiving it, he realized his “parallel world... would be very much like a Victorian society with certain material changes. This would have to be, in some ways, a Victorian novel. [But] since, I had decided it would be a light book, I did not dare even touch on the real condition of the Victorian working class, child prostitution and all the various ills of society at that period. I had to ignore them. So, true to the nature of the book but not true to my own beliefs, it did turn into a Tory vision of glory for which I do apologise to my socialist friends.”

Harrison's remark captures—and prophesies - a large element of the appeal of steampunk as a genre: the old fashioned atmosphere and décor and trappings, but also the old fashioned formal properties (characterization, dialogue, plots, etc that all follow the adventure-hero model of pulp fiction genres or 19th Century popular story-telling – Rudyard Kipling, R. Rider Haggard). That kind of nostalgia or hankering for a supposedly more romantic and dashing time is fused with the thrills and wonder of science fiction, particularly the kind of hard science fiction that fixates on technology. Instead of a straightforward linear advance in technology, it’s a step sideways and then step forwards again, down a different branch of development.

Fans and critics talk of a division

between historical steampunk versus fantasy-world steampunk. In the latter, there

is less emphasis on the historical method and the kind of ironies and reversals

that the altered world generates, and more on the décor of this transformed

world and the kind of adventures it allows for. This division between historical

and fantasy is similar to the difference

between science fiction and science fantasy. In science fantasy - or as it

sometimes called, space opera - it’s essentially a magical world: there are

monsters and dragons, supernatural powers, divination and prophesy, often a

priestly caste of wizards or magi. Think

Dune. And usually there is some kind of quasi-Medieval symbolics to do with

blood, honor, destiny, dynasties, clans, oaths and pledging of fealty. All the

Lord of Rings, Game of Thrones type stuff. This kind of fantasy tends to run on

emotional energies uncomfortably close to authoritarianism. It is fueled by royalist

or outright fascist energies – the desire for a hero strongman, or the desire

to be a hero yourself. Often there is a barely disguised nostalgia for a caste

society, where everybody knows their place in a

stratified and hierarchical society. There is steampunk that is based on

similar sorts of desires and fantasies, and rather than involving historical

thinking and feeling, it’s more about an escape from History, or at least an

escape from our current historical moment.

The result is Jules Verne but without the timeliness and relevance that

Verne had in his own time.

Nicholas Lezard, the British critic, noted that many of the historians who are interested in alternative history - Niall Ferguson, Norman Stone, Winston Churchill - are right wing. There are a lot of counterfactual histories about a world in which the British Empire never waned. And there are an uncomfortably large number where Hitler won World War 2, or the South prevailed in what is in this altered reality now officially known as the War of Northern Aggression. (A delicious spoof on this appetite for Confederate counterfactualism is Sword of Trust, the recent movie, which involves a conspiracy theory underworld of Civil War truthers, who believe that the Northern aggressors really were defeated and there's been a massive cover-up).

Generally, there tends to be a fixation

on Great Men – the idea that a single act by a figure such as Napoleon or Robert E. Lee can change

the course of history.

A particularly vivid example of a nostalgic

alternative history is the novel Ada, by Vladimir Nabokov, which is set in a

world in which the Mongol and Tartars conquered the territory that Russia

comprise. As a result the Russian people ultimately settled in North America.

So the Tsarist world of country homes and servants in which Nabokov grew up is

magically relocated to where he ended up living in exile. In this world, electricity is banned but things are powered mysteriously using a water-based

technology.

"Steampunk Manifesto" by Professor Calamity accused most steampunk of being at best nostalgic escapism, at worst outright reactionary:

“Unfortunately most so-called

“steampunk” is simply dressed up reactionary nostalgia. The stifling tea-rooms

of Victorian imperialists and faded maps of colonial hubris. It is a

sepia-toned yesteryear more appropriate for Disney and Grandparents than a

vibrant and viable philosophy or culture”

The anonymous author of this tirade

calls for a more politically acute version of steampunk alert to conflict and class struggle – “We stand with the traitors of the past as we hatch impossible

treasons against our present.”

Professor Calamity says that the

‘punk’ element is missing – steampunk in truth is far more often steamprog.

Which brings to me to the subject of

counterfactuals in music.

There are numerous bands who identify

as ‘steampunk’, dress the part, and do fairly conventional rock music that

carries steampunk themes or storylines – like Abney Park, an American group

steeped in English imagery. This is is an

extension of the fantasy and cos-play aspects of Goth or metal (Abney Park used to be a Goth

band, in fact).

Far more interesting are groups trying to

imagine sonic forms that could have existed in alternate musical histories.

Add N To (X) were a band of the ‘90s and

early 2000S who used analogue hardware synths at a time when digital technology

was dominant. Their music could be seen as imagining an alternate rock world

where the synth displaced the guitar as the primary instrument and so the future

direction of electronic pop is not hypnotic and trance-like (the Moroder path) but rocking and

bombastic (ELP, Magma etc).

Broadcast imagined a world where all pop descends from a few 1960 psychedelic groups that used synthesisers and had ethereal pure-toned female singers: White Noise and United States of America in particular. A genre I call "synthedelia" - indeed in the piece linked I even do a bit of counterfactual speculation about whether this lost moment of Moog-love in American rock music could have blossomed rather than withering.

With Ariel Pink’s Haunted Graffiti, it’s more the case that individual songs involve strange combinations of the pop past: he described “The People I’m Not” as “a demo from Rocket From the Tombs, but playing a Fleetwood Mac song – there’s some Tango In the Night, ‘tell me sweet little lies’ vibe in there” – in other words, a song and a style that is from a decade-or-more after the Cleveland proto-punk group Rocket from the Tombs ceased to exist. (Pink more recently, and regrettably, has opted for a kind of political counterfactualism, seemingly believing that the 2020 Election was stolen and Trump is the rightful President).

The leading hauntology label in the UK is Ghostbox and its artists often resemble renegade

archivists looking to uncover alternate pasts secreted inside the official

narrative. Take The Focus Group’s album We

Are Pan’s People –here Julian House conducts a kind of alternate-historical research, looking for

hidden possibilities in glam rock, light entertainment and British movie-score

jazz. “Albion Festival Report” is an attempt, said House, to imagine “what

if rock and roll didn't happen, jazz continued

on a strange trajectory. “

Fans for years have been creating

unfinished or unreleased albums like Beach Boys's Smile, Hendrix’s First Rays of

the New Rising Sun, The Beatles's Get Back, the Who’s Lifehouse – using bootlegs,

demos, out-takes, and so forth. Today

there is a whole realm of blogs dedicated to this practice – Albums That Never Were, A Crazy Gift of Time, Albums That Should Exist, Albums I Wish Existed… Usually they create fake artwork for the counterfactual albums.

Some of these blogs, such as Strawberry

Peppers, don’t stop at creating imaginary albums and record covers – they write incredibly detailed and extensive histories of worlds where the Beatles didn’t split up, or

where David Bowie joined the Rolling Stones, or where the Soft Machine’s Kevin

Ayers, Robert Wyatt and Daevid Allen don’t leave the band, or alternate timelines where Syd Barrett

stayed in Pink Floyd. A kind of counter-discographical mania erupts.

So now, winding up, let me return to where I started, this connection between steampunk along with its host genres alternative history and science fiction, and hauntology.

With alternative history, there’s

still that sense of world-turned-upside-down disorientation that science

fiction supplies, but it’s not set in the future or on some distant alien

planet: it’s our world seen in a distorting mirror, made unrecognizable and even

grotesque.

Fredric Jameson is renowned as a great

theorist of postmodernism. But he has also written extensively about science

fiction in his book Archaeologies of the Future: the Desire Called Utopia and

Other Science Fictions. He is a real sci-fi nerd in fact, with deep knowledge of even its pulpiest thoroughfares. But in that

book, Jameson doesn’t discuss alternative history much, even though in his Marxist

writing he’s constantly going on about dialectical materialism and historical

thinking. In another book, though, when talking about Derrida

and the concept of hauntology, Fredric Jameson defines “spectrality” as that

which “makes the present waver: like the vibrations of a heat wave through

which the massiveness of the object world--indeed of matter itself--now

shimmers like a mirage.”

I think that effect is what the best alternative history does: it makes our world seem ghostly, makes the present waver and reality seem unreal, insubstantial.

Another thing it does is activate a sense of history as changeable - in both the sense of being volatile, but also subject to human agency and will. Alternative history, including steampunk, can at its best counteract that waning of historicity that Jameson identifies as a symptomatic hallmark of postmodernity, that fatalistic feeling that the world is as it only can be ; the era of revolutions or even progress is over. It subtly resists the “The End of History” argument of Francis Fukuyama: no more ideologies, liberal democracy and globalized capitalism triumphant for ever more.

You come away from reading a book like The Difference Engine or Pavane with a sense that things could have gone differently, and that therefore things could go differently in the future. Nothing is ordained, nothing is predestined.

Alternative History tends to fixate on turning points – in Moore's marvelous Bring the Jubilee it's one decision by a soldier in a field during the Battle of Gettysburg that then determines the course of the battle, and thus the outcome of the American Civil War.

In that sense, Alternative History is anti-deterministic

– it believes in the Event. In human free will – in human agency but also human

error - in the role of accident and

contingency.

The word ‘alternative’ makes me think

of Mark Fisher’s book Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?

Alternative History, at its most provocative and unsettling, is saying "yes, there is an alternative, because in the past, there could have been alternatives –

things could have gone better, or worse, or just radically different".

One recent addition to that category of politically provocative alternative history was published by Repeater Books, the radical publisher Mark Fisher co-founded – Eminent Domain, by Carl Neville . This novel imagines a world where Soviet Communism triumphed but also managed to reform itself and liberalize itself. In this world The People’s Republic of Britain is a particularly free and experimental nation on the fringe of the Soviet sphere. *

Eminent Domain is that rare thing – an alternative history that is utopian or near-utopian.

Usually, the turning point has turned

to the worst – Nazis rule the world, or there’s a Confederate

States of America.

But in Eminent Domain, things have

come out better – the novel imagines all kind of liberating and innovative developments

in the organization of work and leisure, human potential optimization through the

use of drugs and new kinds of technology.

Reading Neville’s book makes you

conscious of the radical potentials dormant in our present, the different way

things could be.

After finishing the book, there is a

curious unsettling sensation that this present in which we currently languish is

the imposter reality – that this world is the Counterfeit World.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

* (Eminent Domain is loosely related to Neville's very-near-future s.f. Resolution Way, in which one thread involves a hauntology-flavored subplot about a mythological lost recording by a mystery-shrouded musician. So these two related modes of historical thinking in speculative fiction are here entangled with ghost story aspects).